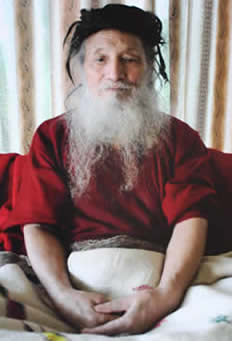

I would like to tell a story about Amtin, a remarkable yogi who lives in Tashi Jong, northern India. His spiritual tradition is the Drukpa Kagyu, but his practice is Nyingma, Dzogchen, like me. When he lived in Tibet, he practiced meditation a lot and became very peaceful. He stayed in solitary retreat for six years, and the retreat situation was very comfortable, very nice. In those days, people would bring food to yogis on retreat, or the yogi had his own ingredients–he could cook up a nice little meal for himself. There was lots of firewood around; when the sun was shining, it could be quite warm; and one might even see a wide-open vista of sky. There were trees all around and various animals could be seen in the forest.

The yogi might have some pride: ‘I am practicing the Dharma. I am very happy; it is very comfortable for me here. There are no negative emotions, no difficulties, no obstacles. I’m still young.’ After six years, Amtin felt that his practice was going very well, indeed. But then he thought, ‘Well, who knows, maybe this practice has just turned me into a tranquil vegetable.’ So he asked his master, Khamtrul Rinpoche, ‘Wouldn’t it perhaps be better if I went to a scary place, a rough, rugged, unpleasant place?’ Khamtrul Rinpoche said, ‘Yes, definitely, you should go to such a place,’ and he gave directions to a particular location.

Arriving there, Amtin found a huge cave where the sun never shone, with water trickling down the entrance. In the evening, a large flock of pigeons flew around inside, making a lot of noise while shitting down on him. The first day he didn’t know what was going on. He put out various containers to collect the water trickling down, but when he drank from it, he said, ‘What is this? It has a strange taste.’ Later he realized it was urine from the pigeons. The cave was cold and damp, noisy, and scary at night. As he practiced there he found that his former peace of mind was tracelessly gone. He thought, ‘My practice has gone to pieces. Now what should I do?’ And he felt that whatever he had done in the past didn’t amount to much, so now he really had to practice.

It was very difficult in the beginning, with the restless pigeons flying around in the dark. It was like being in the bardo, with all the turmoil and noise. Amtin tried to cultivate this inner strength of rigpa by not surrendering himself to the distraction, by not getting carried away with the noise. He trained like that over and over again. He stayed in that place for maybe another six years. And now, whatever happens, whether it is pleasant or unpleasant, really doesn’t affect him. He doesn’t care anymore. But that doesn’t mean that he ignores everything. I believe that when Amtin dies, he probably won’t have that much trouble in the bardo. For him, all emotions are, as they say, subsumed within the expanse of rigpa. In other words, he’s free.

Epilogue

At the age of 84, Togden Amtin passed away peacefully in Tashi Jong, India on Friday, July 1st, the 25th day of the fifth Tibetan month, Dakini Day. Dorzong Rinpoche, Choegyal Rinpoche, and Tsoknyi Rinpoche were with him when he passed. Tsoknyi Rinpoche arrived in Tashi Jong at about 2 p.m. that day and went straight to Togden Amtin’s room. Choegyal Rinpoche was already there. Dorzong Rinpoche arrived a few hours later. The three of them were beside Amtin in his final hours. The atmosphere was very calm, and the process of dying happened very smoothly. Earlier on, Togden Amtin experienced some pain, but this passed. In his final moments, Togden Amtin was very much at peace, just like a flame slowly fading. From time to time he opened his eyes, and his gaze was very direct and clear although he no longer had enough power in his body to speak or move.

Just before Togden Amtin’s passing and at the moment of his death, Dorzong Rinpoche whispered instructions in his ear: a reminder of the natural luminosity of mind. At 7:15 p.m., Togden Amtin died. He remained in tugdam for one-and-a-half days; very subtle vital signs were evident. No one went inside his room and the outside was kept very quiet. That night under the cover of darkness, the young togdens came and sat outside Amtin’s hut, mingling their minds with their teacher’s as they said their silent good-bye. When Togden Amtin’s tugdam was finished, all the Rinpoches and monks at Tashi Jong came to pray and offer khatas. The atmosphere was very calm. They prayed the Mahamudra prayer and mingled their minds with their teacher’s. The lay community then arrived to pay their final respects.

Togden Amtin dedicated his life to intensive yogic training at Tashi Jong. Though traditionally togdens only pass their teachings on to the younger togdens of their lineage, through his great kindness Togden Amtin taught and gave instructions to students from all over the world. While at Tashi Jong, Tsoknyi Rinpoche was fortunate to receive teachings from him and realize a strong karmic connection. Tsoknyi Rinpoche considered Togden Amtin to be his second Dzogchen teacher, after his father, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche. Following Togden Amtin’s death, Khamtrul Rinpoche has agreed to officially begin teaching.

Until we reach that level, we need to practice. We must grow used to this freedom. Use as a yardstick your ability to cope with whatever emotion arises. We must transcend being hijacked by the current emotion, being on the defensive against it, or trying to get rid of it. We reach this gradually, as we become more and more stable and confident in empty essence, cognizant nature, and unconfined capacity. Then we discover that the emotion does not necessarily run us over, and we don’t need to get caught up in it either. We don’t have to prevent or suppress the emotion. Rather, we simply allow it, spontaneously and naturally, to become an embellishment of rigpa.

Fearless Simplicity, pp. 186-187